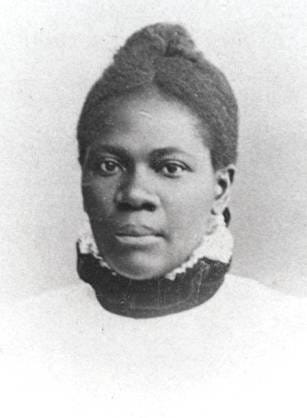

Fannie Lou Hamer was a black civil rights activist who fought not only for black people. but for black women.

She was born on Oct. 6, 1917 in Rulesville, Mississippi to a pair of sharecroppers (individuals who use land on somebody else’s plantation or farm and give them a portion of the crops grown in return) and grew up in poverty.

She joined her family picking cotton at the age of 6, and left school at the age of 12 to work. Because she could read and write, she served as plantation timekeeper. Since they couldn’t have children, they adopted four girls.

She married in 1945 to Perry “Pap” Homer, and the couple would work on that plantation for another 18 years.

Hamer and Homer wanted to start a family very badly, but in 1961, while she was having surgery to remove a tumor on the lining of her womb, a white doctor removed her uterus without her consent.

This practice of forced sterilization was common in Mississippi at the time and was used to control the population of poor African American people. According to an article by the Washington University Department Of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hamer coined it as the “Mississippi Appendectomy”, and found that 3 out of 5 of all black women in her hometown community had underwent one

According to a now archived document written by the Amistad Research Center, Hamer became interested in the civil rights movement in the 1950’s, and heard local leaders of the movement speak at conferences , where they discussed Black voting rights.

In 1962, she and 17 other Black people went to vote, but failed the literacy test. She went to a courthouse in Indianola, where she tried again, and she failed again. On Jan. 10, 1963, she took the test again and passed; but when she went to vote, she was still turned away.

She didn’t have the requisite poll tax receipts, a requirement that had only emerged in some southern states after all races had been granted the right to vote by the 1870’s ratification of the 15th amendment.

After her first attempt to vote, Hamer was fired from the plantation she used to work on, but her husband was forced to continue working until the end of that year’s harvest.

After these incidents, Hamer became involved with SNCC, and began traveling to gather signatures for petitions to attempt to grant federal resources to impoverished Black families across the South.

She became a field secretary for voter registration and welfare programs. Then, in 1963, she attempted to register more Black voters in Mississippi, but she would be met with the same racist walls she previously faced.

According to an archived article from Mississippi “HistoryNow”, on June 9, 1963, Hamer was returning from a SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference) voter workshop. She was traveling with other activists by bus, and they were stopped in Winona, Mississippi.

They went inside a local cafe, but were refused service. A Mississippi State Officer soon came in and intimidated the group into leaving by tapping them with his club, saying “Ain’t no d*** law, you just get out of here!”

On the way back to the bus, an activist in the group wrote down the license plate number of the officer, after which the patrolman and a police chief arrested the party. Hamer came out from the bus to ask if the group was still continuing to their next destination and was arrested as well.

She, and one 15 year-old June Johnson, were beaten in the booking room for not addressing the officers as “sir”. Then, she was taken to a cell, held down by police officers, and further assaulted by two inmates who had been ordered to beat her with batons.

According to a book titled “At the dark end of the street”, authored by Danielle L. Mcguire, and Hamer’s own words, when she began to scream, she was beaten further. She was groped during the assault, and when she attempted to resist, had her dress flipped over and body revealed to the inmates and police officers.

According to another book titled “SNCC: The New Abolitionists”, authored by Howard Zinn, and a book titled “God’s long summer ; stories of faith and civil rights” by Charles Marsh, another in her group was beaten until they were unable to talk, another teenager was beaten, stomped on and stripped, and when a SNCC activist came to see if they could help, they were beaten until their eyes were swollen shut, as they also did not refer to the officers with the correct titles.

When Hamer was finally released, it took her a month to recuperate from the beatings, and she would never recover from the blood clot in her left eye and permanent damage to one of her kidneys.

Despite the extensive psychological damage this undoubtedly had on Hamer, she continued to organize voter registration drives. In 1964, she co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in order to prevent the regional all-white democratic party from stifling Black voices.

Following the founding of the MFDP, Hamer travelled to the 1964 Democratic National Convention. and her testimony was broadcast to the entire nation. An excerpt from her testimony:

“If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives are threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings in America?”

Senator Hubert Humphery, who previously stated that “The President will not allow that illiterate woman to speak from the floor of the convention” when told of the fact that Hamer was being considered, offered two seats to the MFDP.

When they refused, all the white Mississippi delegation walked out. The MFDP would not be seated until 1968, after the Democratic Party adopted a clause that demanded equality of representation from the delegation of states.

Also in 1964, Hamer attempted to run for a seat in the U.S House, but failed. Still, she continued to help with many other projects, such as Martin Luther King Jrs. Poor People Campaign.

She created the Freedom Farm Collective in 1969 in an attempt to solidify African American peoples standing and economic power in agriculture in opposition to James Eastland, a white senator who sought to keep Black people segregated from society and agriculture (according to an article from the Digital SNCC Archive).

She partnered with the National Council of Negro Women to establish an interracial and interregional support program named the Pig Project. The Pig Project was a pig bank in which families could care for a pregnant female pig until it bore a child, then raise the piglet either for food or for financial gain.

Within five years, thousands of pigs were available for breeding. Hamer used the success of the Pig Bank to raise funds for the FCC, and after raising $8,000, she purchased 40 acres of farmland from a Black farmer and used it to establish an agricultural organization.

The FCC would grow in scope, though, eventually offering financial counseling, a scholarship fund and a housing agency. Through this growth, the FCC would secure 35 houses subsidized by the Federal Housing Administration for struggling Black families. Unfortunately, the FCC would eventually dissolve in 1975 due to a lack of funding.

On Mar. 14, 1977, aged 59, Hamer died due to complications with hypertension and breast cancer.

There are thousands of activists, just like Hamer, who didn’t have massive, history altering success in changing the world around them, and hundreds of thousands of activists like the many SNCC members around her who’s actions would never directly cause any change.

And yet, they all paid the heavy, heavy price of activism at every turn. Change is not built off of peaceful memories and gentle prodding, but off of the constant pouring of blood, sweat, and tears of women and men like Hamer.

“I guess if I’d had any sense, I’d have been a little scared—but what was the point of being scared? The only thing they could do was kill me, and it kinda seemed like they’d been trying to do that a little bit at a time since I could remember.” – a quote from Fannie Lou Hamer, pulled from James MacGregor Burns’ “Crosswind Of Freedom”.

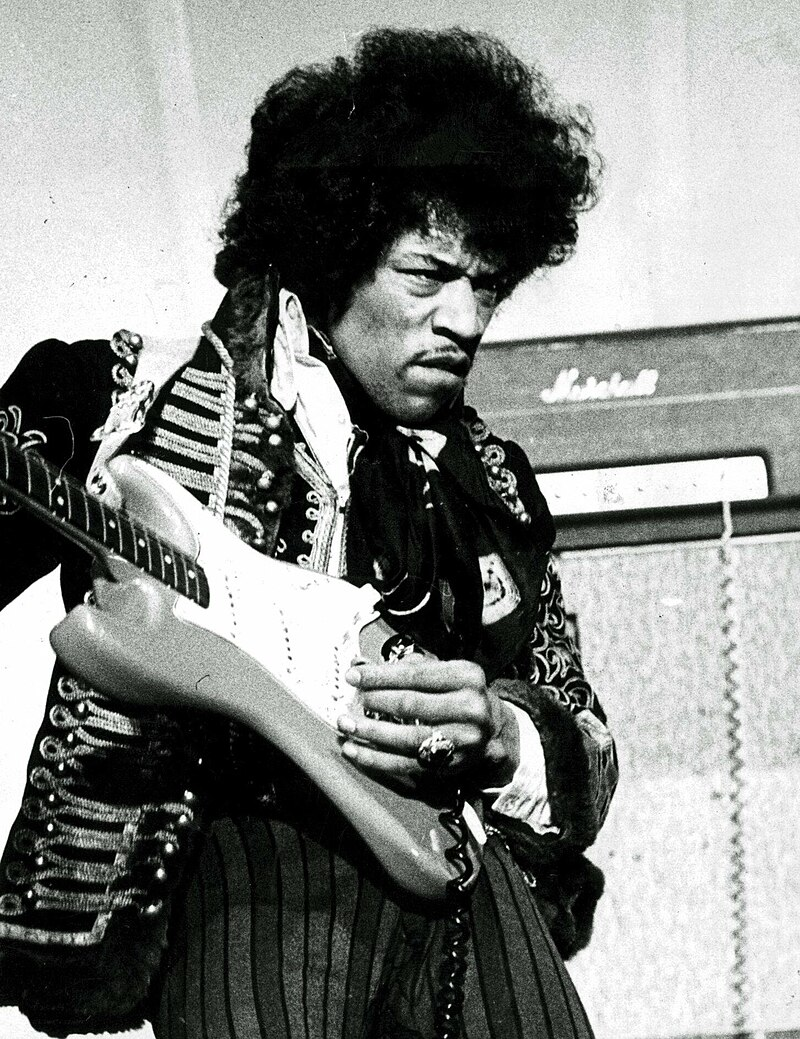

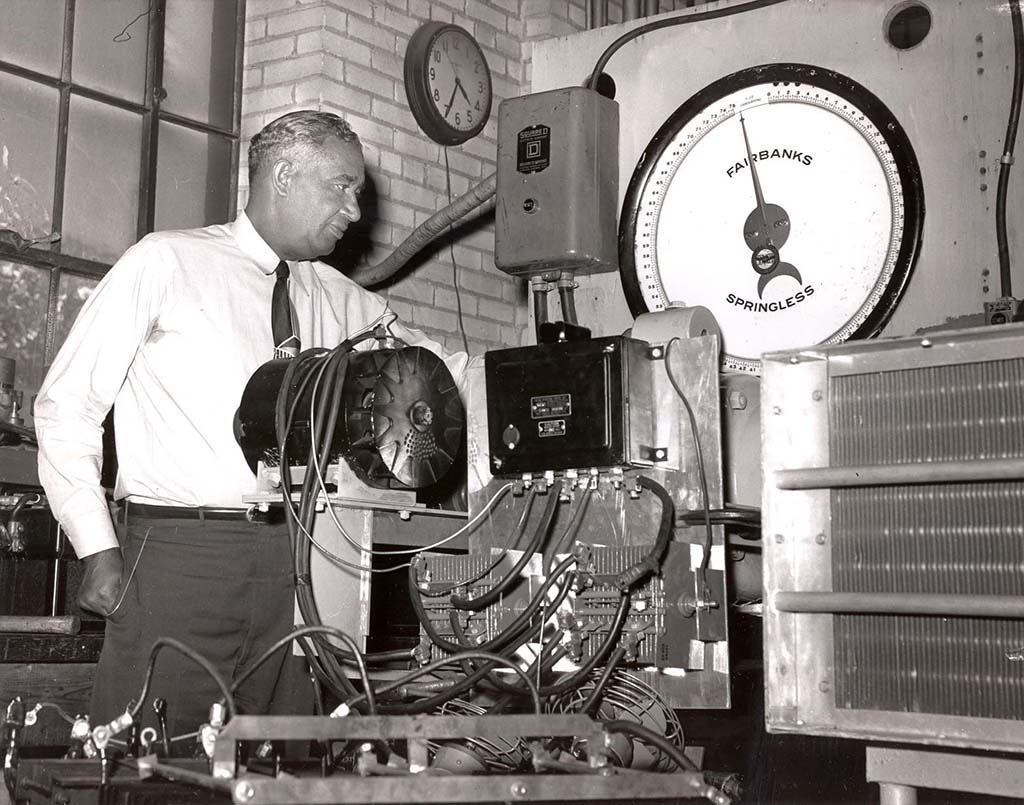

Thank you for experiencing the stories of all of these amazing Black people with us. From minor civil right activists, to massive legends of athletics and music performance, all of these people have had a distinct impact on Black History, to an extent that could never be measured.

Many of these people didn’t have an amazing education, and those who did had to fight white supremacists and violent racism for every inch of learning. Many of these people didn’t know they’d change the world, until it was already changed.

People today hold the power to create change just as much as the magnificent 28 individuals highlighted this month did; just as much as the hundreds of thousands of impressive Black figures in Black History did, and you will always, always have that power.

It doesn’t matter your age, or your size, or how smart you are, or how strong you are, or whatever. Change begins with you. And, if you don’t know where or how to start, start with these 28, and build a legend of your own. Thank you again, and Happy Black History Month!